An article in New Indian Express, Chennai, today

Prashanti Ganesh

Express News Service

Last Updated: 21 Feb 2012 10:32:30 AM IST

CHENNAI:

Who can really say 'No' to desi a parody of P G Wodehouse? Especially

if the British author's favourite protagonist Jeeves becomes Jeevan!

Saaz Aggarwal, Mumbai-based humour columnist's book The Songbird on my

Shoulder, Confessions of an Unrepentant Madam has that and more. The

book is a potpourri of short stories, poems and columns that she has

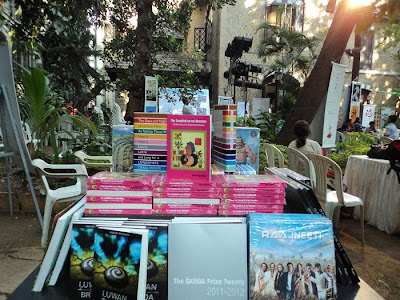

accumulated over the years. When she was recently at Landmark, Citi Centre, to release her book in the city, she did convince that if there were these certain pieces of writing that did make it to the book, there were a ton of others that didn’t. The book is Saaz's take on various incidents that have taken place in and around Mumbai and Pune and also has more personal writing, that dwell upon touchy topics of being a stepmother and being obese, among other things. Discussions about the book were meagre, not counting the unconventional amount of reading from the book that took place (all through which Saaz meticulously rolled her eyes). And finally, even Saaz felt she owed something to the audience who had braved the traffic to pick up a copy of the candy pink-covered book.

“I often write something, see it on the

page and I ask myself where it came from. I wrote a poem when I was

still a kid and tried to articulate the feeling of where it was coming

from. I then realised that it was the songbird,” she explained. The

songbird is definitely not her muse, she pointed out.Saaz did put

a caricature of sorts of herself on the cover of her book, with

red-rimmed glasses, so there's no doubt that she does consider herself

to be a ‘madam’ of sorts. “When I was putting the material together, I

noticed that I referred to myself as ‘madam’ in a sarcastic way many

times. So, I thought it will be funny to play on this aspect of the word

and used on the title.”She felt like laughing at the sight of

her books on the stands, Saaz admitted. “I can’t believe this is

happening. I’m happy that I did the book, but I’m just really waiting to

see what happens,” she said.

“I often write something, see it on the

page and I ask myself where it came from. I wrote a poem when I was

still a kid and tried to articulate the feeling of where it was coming

from. I then realised that it was the songbird,” she explained. The

songbird is definitely not her muse, she pointed out.Saaz did put

a caricature of sorts of herself on the cover of her book, with

red-rimmed glasses, so there's no doubt that she does consider herself

to be a ‘madam’ of sorts. “When I was putting the material together, I

noticed that I referred to myself as ‘madam’ in a sarcastic way many

times. So, I thought it will be funny to play on this aspect of the word

and used on the title.”She felt like laughing at the sight of

her books on the stands, Saaz admitted. “I can’t believe this is

happening. I’m happy that I did the book, but I’m just really waiting to

see what happens,” she said.Photos courtesy Landmark